“Every afternoon, Kafka goes out for a walk in the park. More often than not, Dora goes with him. One day, they run into a little girl in tears, sobbing her heart out. Kafka asks her what’s wrong, and she tells him that she’s lost her doll. He immediately starts inventing a story to explain what happened. ‘Your doll has gone off on a trip,’ he says. ‘How do you know that?’ the girl asks. ‘Because she’s written me a letter,’ Kafka says. The girl seems suspicious. ‘Do you have it on you?’ she asks. ‘No, I’m sorry,’ he says. ‘I left it at home by mistake, but I’ll bring it with me tomorrow.’ He’s so convincing, the girl doesn’t know what so think anymore. Can it be possible that this mysterious man is telling the truth?

“Kafka goes straight home to write tha letter. He sits down at his desk, and as Dora watches him wite, she notices the same seriousness and tension he displays when composing his own work. He isn’t about to cheat the little girl. This is a real literary labour, and he’s determined to get it right. If he can come up with a beautiful and persuasive lie, it will supplant the girl’s loss with a different reality – a false one, maybe, but something true and believable according to the laws of fiction.

“The next day, Kafka rushes back to the park with the letter. The girl is waiting fot him, and since she hasn’t learned how to read yet, he reads the letter out loud to her. The doll is very sorry, but she’s grown tired of living with the same people all the time. She needs to get out and see the world, to make new friends. It’s not that she doesn’t love the little girl, but she longs for a change of scenery, and therefore they must separate for a while. The doll then promises to write the girl every day and keep her abreast of her activities.“That’s where the story begins to break my heart. It’s astonishing enough that Kafka took the trouble to write the first letter, but now he commits himself to the project of writing a new letter every day – for no other reason than to console the little girl, who happens to be a complete stranger to him, a child he ran into by accident one afternoon in a park. What kind of man does a thing like that? He kept it up for three weeks, Nathan. Three weeks. One of the most brilliant writers who ever lived sacrificing his time – his ever more precious and dwindling time – to composing imaginary letters from a lost doll. […]” Paul Auster - The Brooklin Follies

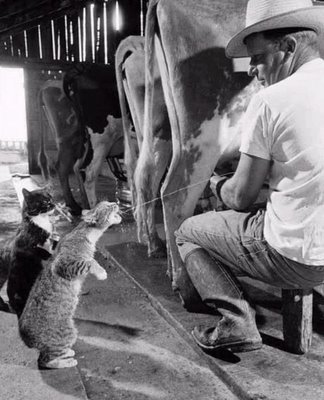

Alfred Sieglitz

...

...